Concrete surface treatments must be selected and validated based on operational loading cycles, not appearance or short-term durability metrics.

In automated facilities, floor performance does not degrade randomly it degrades predictably. The rate and pattern of that degradation are determined early, long before autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) begin operating at scale. One of the most influential and frequently misunderstood variables in this lifecycle equation is concrete densification.

Densification is not a cosmetic treatment. It is a chemical process that alters the near-surface zone of hardened concrete, directly affecting abrasion resistance, micro-scale flatness stability, dust generation, and long-term interaction with robotic wheels. In automation heavy environments, these factors translate into navigation consistency, sensor reliability, maintenance frequency, and total cost of ownership.

AMRs and automated storage systems impose repetitive, localized loading along fixed paths. Unlike forklifts, these loads are lighter but vastly more frequent, producing cumulative wear that concentrates along navigation corridors. Without sufficient surface densification, this wear manifests as fine dust, micro-raveling, and surface polish loss conditions that interfere with optical sensors, reduce wheel traction predictability, and accelerate floor deviation over time.

The misconception is that densification is primarily about hardness. In reality, its operational value lies in surface stability. Properly densified concrete resists paste erosion, maintains a tighter pore structure, and preserves floor geometry under repeated robotic traffic. Poorly densified or incorrectly applied systems can fail silently, offering early visual appeal but degrading rapidly under automation loads.

From an engineering standpoint, densification should be treated as a performance modifier, not a finish. Its effectiveness depends on slab maturity, surface preparation, traffic modeling, and validation testing. When aligned with automation requirements, densification extends usable floor life, stabilizes FF/FL performance, and reduces downstream operational risk. When misapplied, it becomes an invisible failure point embedded into the slab.

How Concrete Densification Works at the Wheel Floor Interface

Concrete densifiers are typically silicate based solutions that react with free calcium hydroxide in the cement matrix. This reaction forms additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), reducing capillary porosity in the surface zone. The result is a denser, less friable layer where robotic wheels make continuous contact.

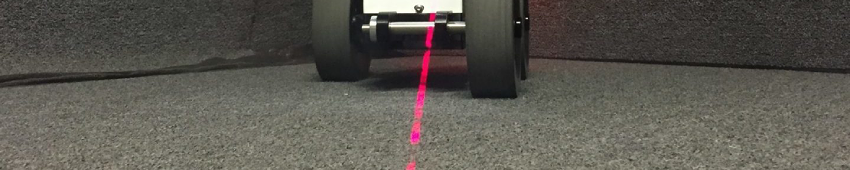

For AMRs, this interface governs traction consistency and rolling resistance. A stable, densified surface minimizes micro-pitting that can cause subtle speed variations or wheel slip events small effects that compound over thousands of navigation cycles. In high precision environments, these deviations affect path repeatability and localization confidence.

The key variable is penetration depth, not surface sheen. Shallow reactions produce short-lived improvements, while properly absorbed densifiers reinforce the load bearing surface zone that experiences the highest shear stress from robotic wheels.

Densification vs. Polishing in Automation Driven Environments

Densification and polishing are often conflated, but they serve distinct roles in automated facilities. Polishing refines surface texture; densification modifies material behavior. A polished but under densified slab may initially meet visual and flatness requirements, yet deteriorate rapidly under repetitive robotic traffic.

Automation systems are indifferent to gloss. They respond to friction stability, dust suppression, and surface continuity. Densification addresses these parameters directly by reducing paste breakdown and limiting fine particulate generation that interferes with sensors and drive components.

In lifecycle terms, densification is a risk control layer. Polishing without sufficient densification front loads appearance while back loading operational failures.

When and Where Densification Matters Most

Densification impact is not uniform across a facility. It is most critical in high-frequency travel lanes, docking zones, and charging areas where robots decelerate, pivot, or dwell. These zones experience higher shear forces and localized abrasion.

Applying a uniform densification strategy without considering traffic density leads to uneven performance. Engineering-led programs adjust application rates, surface prep, and verification methods based on predicted robotic behavior not square footage alone.

Facilities that fail to align densification strategy with automation layout often experience early wear patterns that are difficult to remediate without operational disruption.

Testing and Validation of Densified Floors for Automation

Densification performance must be verified, not assumed. Hardness tests alone are insufficient. Validation should include abrasion resistance, dusting potential, and post treatment flatness retention under simulated traffic where possible.

Standards such as ASTM abrasion and wear tests provide comparative baselines, but automation specific interpretation is required. The goal is not maximum hardness it is predictable behavior under repetitive, low-load cycles.

A densified floor that maintains geometry and surface integrity over time directly supports automation uptime and reduces long-term maintenance intervention.

Common Densification Failure Modes in Automated Facilities

Failure rarely presents as sudden damage. More often, it appears as gradual dust accumulation, subtle wheel tracking, or increased cleaning frequency. These symptoms are frequently misattributed to housekeeping or robot calibration issues rather than surface chemistry.

Typical root causes include premature application on immature slabs, insufficient surface preparation, or mismatched densifier chemistry relative to cement composition. In automation environments, these errors propagate silently until operational efficiency is affected.

Understanding densification as a system input not a finishing step is essential to avoiding these failures.